Growing up with the Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra

1966 – 1971

YOUTH MAKES MUSIC

Growing up with the Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra

Philip Monk

Preface

I suppose the idea is a bit strange. Why on earth would I choose to write about my childhood after all this time?

Well, in truth, it’s because I believe that I had a special childhood. Not because I’m special, but because I was part of something that was very special – the Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra.

Obviously it’s easy to be nostalgic at this time in my life. There’s sometimes sorrow at the loss of one’s youth, and a tendency to believe that things were better in those times than they actually were. But this short story isn’t just an exercise in sentimentality. It’s my own very personal account of what it was like in those days to be part of the County School of Music and play in the Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra. It’s my own private way of paying tribute to the orchestra and to Eric Pinkett.

Perhaps I believe that once I’ve finished it I can see those days within some sort of lifespan context and come to terms with where I am now, and what I may do in the future. Perhaps I rather hope that other close friends who were part of this period in my life will read it, enjoy some of the stories, and remember the good times that we had together. But my overriding motivation is an inner urge to set something down on paper about those days before I forget the details altogether. I’ve got other projects planned and I can’t seem to give them my complete concentration until I’ve fulfilled this strange need to put the story into words and my record of those days is complete.

Were those of us who were musicians different to other kids? I’m convinced we were. Other children had their mates, their football and their Boy Scouts, and so on. But I don’t think these activities stand comparison, even taking into account my own perspective. It’s not just how close we all were; it’s about the uniqueness of exploiting a talent and working together to create an entity that was so very special. It’s not an experience that you can replicate in adult life because of the timely convergence of enthusiasm, youthfulness, and innocence. Even if some of us are still musicians today, it’s not quite the same thing.

I’ve thought long and hard about including my own personal relationships. Perhaps I should have just written a straight account of what it was like to be in the orchestra at that time. But the difficulty is that I can’t separate the two. If this offends some and amuses others, then I offer my apologies to the former group, and the latter won’t mind anyway.

But everything I’ve written is how I remember it even if I impose my own subjectivity. Certain events took place that I’m not so proud of now and, in retrospect, some of them even make me wince with embarrassment. But that’s the whole point about growing up and the integral childishness and immaturity of youth. We all make mistakes at that age; how else do we learn?

Why bother with all this when Eric did such a good job in his book, Time to Remember? Well, Eric told the story of the County School of Music, and of the way in which he managed to turn his vision into reality, together with his own part in creating such an astonishing and marvellous organisation. I don’t seek to compare with his own record of events, except perhaps to re-emphasise his own contribution by adding some further insight into the scope of his achievement.

My story is merely told from the perspective of one of the hundreds of children who have played in the Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra. It’s only one small part of the tale that continues to this day. It’s about the one thing that Eric couldn’t know – what it felt like to be one of the players; what went on behind the scenes; and, most of all, what it meant to spend one’s youth growing up with classical music.

Acknowledgements

1) My thanks to friends for their help in checking my facts and correcting my mistakes. In addition, in some passages, their own memories and anecdotes have helped refresh my memories.

2) Particular thanks must go to Dave Smith who allowed me to reproduce some of the many photographs that he took of the orchestra over the years, and John Whitmore who checked and corrected some of my dates, places and other details.

3) Where I’ve mentioned the names of certain girls at various places in the book, I’ve gained their permission to do so – if I’ve been able to contact them. Wherever I haven’t obtained such approval, I’ve respected their anonymity.

Notes

1) In the text, where a number in bold appears thus (17) after a concert date, it refers to the corresponding program number in Appendix A. In turn, this program number shows details of the actual program performed on that specific day.

2) My apologies for any omissions in the lists of players. It’s difficult to say precisely who was in the orchestra at a specific point in time since there were always at least one or two players in the process of joining or leaving.

Chapter One

1961-1963

It was my Dad’s idea. I’m not sure why he decided to take me to Market Harborough Town Band at the tender age of nine and ask them if they would teach me to play the cornet. Perhaps it was his own love of music or maybe he thought I’d be the next Louis Armstrong. Anyway, I did what I was told and went along to our local band, where I was introduced to the bandmaster and shown how to hold a cornet. By the end of the first practice session I had managed to blow a primitive note on it, and, to my surprise, was even allowed to take home a battered instrument and an old scale book. I was the newest recruit to a small band of six children whom the bandmaster, Mr Yarrow, would teach twice a week before the senior band rehearsal started.

I wasn’t that keen really. It appeared to me that playing with my friends outside was much more fun, especially as I began to appreciate how difficult it was to master the instrument. I would have given up but my father was determined to make me continue, even to the extent of refusing to allow me to go out to play until I’d completed my compulsory thirty minutes practice every evening.

So my Dad took me from our house in Gumley to band rehearsals in Market Harborough twice a week, and the combination of this attendance – together with his persistence in making me practice – eventually began to pay off. I still couldn’t manage more than a few simple tunes and scales but it didn’t sound quite so much like a ship’s foghorn as it had done previously. My playing slowly started to improve and I began to grasp the rudimentaries of musical notation.

By 1962 I had improved enough to join the senior band. I was allocated to the second cornet bench alongside a boy called Glenn Pollard.

I was ten years old in May and, shortly afterwards, was asked to play in a concert for the first time. On June 24th, the band was to be one of the guest bands invited to play on the bandstand at Northampton’s Abington Park.

The incident that I remember most from this occasion wasn’t the actual performance of the band. During the interval, all the boys were allowed to play golf on the putting green. We had only got to the second hole when a boy swiped his club at the ball, missed, and hit a twelve-year old cornet player named Colin Downes behind the ear. Colin’s wound was soon pouring with blood while the rest of us stood there aghast as it ran onto his shirt and uniform. He had to be taken to hospital to have the cut to his head stitched up and I have never stood behind someone playing golf ever since.

The improvement in my standard of play continued and I began to enjoy the instrument a little more than I had previously. I got the scales off pretty well and started to tackle some of the more difficult pieces. I still needed my Dad’s occasional coercion to make me practice, but now and again I would pick up the cornet myself without needing to be told.

By the Easter of 1963, although I was not yet eleven years of age, I was deemed ready to play in my first senior band contest at the De Montfort Hall in Leicester. These were the annual area qualifying rounds for the national championships that are held at the Albert Hall in London, and other venues, in October. Competition was stiff and we weren’t placed in the top four – the minimum result to go through to the nationals.

We gave various concerts in the summer and, by the autumn, Mr Yarrow decided that some of the youngsters should become accustomed to the contest atmosphere by entering four of us in a junior quartet competition. He must have thought we were reasonably proficient because he entered us in the Junior (under 15) Championships of Great Britain to be held in Coalville on the 21st September. To our astonishment, our quartet came 5th and we each received a medal. Fifth in the UK under 15! I was astonished at our achievement and even more determined to improve my own standard of play.

The next week our quartet was entered in the Northamptonshire championships, but on this occasion I was also invited to take part in a solo contest for the first time. The event took place on the 28th September at the Kettering Rifles Band clubroom.

I was too nervous to do well and dried up completely. Even worse, later in the contest another youth played the same piece that I had chosen – but immaculately – and won the contest. His name was Jimmy Watson. He became the champion cornet player of Great Britain two years later (both the Junior and Senior in the same year) and became quite famous as a performer and conductor. Little did I know then that he and I would meet again in very different circumstances.

Our quartet failed to be placed this time but, undeterred, we put our name down for the next competition at the same venue.

However, the most important event of the year had already taken place; I passed my eleven plus exams and by September had moved on to attend Market Harborough Grammar School.

Chapter Two

1964

I’d spent the Autumn 1963 term getting used to the complete change of environment in my new school. But in the early part of the following year I gradually became aware that there was an orchestra at the school. I heard them play one day in assembly; they were not good to listen to.

I thought about whether to tell the music teacher that I could play an instrument or not, having to judge whether the disadvantages of being part of something as awful as the school orchestra was worth the opportunity to show off. There was another reason why this was a decision that I couldn’t take lightly. I was a cornet player and proud of it. I could see that if I joined the orchestra I would have to play the trumpet. I rather despised the trumpet at the time because I knew that trumpet players played with a ‘straight tone’. I’d spent the previous two years cultivating a ‘vibrato tone’. Cornet players aspire to this type of tone (because it originally imitated the vibrato of singers) and it is therefore considered highly desirable in the brass band world. However my mind was made up for me one day when the teacher asked in class whether anyone would like to join the School Orchestra and I decided to take the plunge.

One of the unfortunate side-effects of my practice and my consequential accomplishment at a comparatively early age was that I was a bit of a big-head! I didn’t really appreciate at the time that the only reason that I had achieved any level of skill at all was not due to some inherent talent but that my Dad had forced me to practice or else! Anyway, joining the School Orchestra seemed like a good way of showing off even more than I usually did, so I told the teacher that I could already play the cornet and he invited me to give him a demonstration. Afterwards, he said that I should not only enrol in the School Orchestra but also join something I’d never heard of called the ‘County Orchestra’. He arranged for me to stay late after school the following week and play for a certain Mr Neale who was a County Orchestra music teacher.

In due course I met Mr Neale and he heard me play. As a result he invited me to join his military wind band, I agreed readily, and from that day onwards took part in the wind group rehearsal every Tuesday evening. Being very confident of my own prowess, I overwhelmed the other players and played twice as loudly as the rest of them put together. After four weeks of this he called me up to the front of the group. Expecting praise, I was slightly embarrassed to hear him say:

‘Philip, you’re on a long sloping hill and you’re tumbling to the bottom. At the bottom of the hill there’s a big ‘D’. One day you’ll slide all the way to the bottom of the hill and you’ll recognise the ‘D’. And do you know what the ‘D’ stands for?’

‘No’, I replied.

‘Discretion’.

I hadn’t the faintest idea what he was talking about.

Anyway, on my first rehearsal with the School Orchestra I was in for a big shock – I wasn’t as great a player as I thought I was! Although the rest of the orchestra was pretty awful, there was a girl trumpeter who was red-hot and much better than me! Her name was Diane Henderson. She was three or four years older than me and played in the County Orchestra. I remember asking her how often she practiced and she replied one hour every night for the trumpet and an hour on the piano without fail. My God!

In no time at all she got me and the rest of the brass players organised and we were soon having regular brass ensemble practices after school.

————-

In the meantime I was back again in the annual solo brass band contest at the Kettering Rifles club. Even though I played quite well, Jimmy Watson was there again in the Junior contest and came first. It was a surprise to me that his brother Bobby, an excellent tenor horn player, pipped him at the post to win the overall open solo section.

————-

After a few weeks in the wind band, Mr Neale invited me to join the County Orchestra. I wasn’t quite sure what this involved but it sounded interesting. Eventually, the day came for my first rehearsal and my father took me to Market Harborough to catch one of the buses that took children to the regular Saturday morning orchestra sessions at Birstall. Someone on the bus told me that there were three orchestras – Junior, Intermediate and Senior but I wasn’t sure which group I was supposed to be playing with. I arrived, very nervous, knowing no-one and equally ignorant about where to go or what to do. Someone must have taken me under their wing because I duly found myself sitting n an orchestra at the end of a row of about seven trumpet players.

It transpired that I was in the Junior Orchestra but no-one appeared to pay any attention to me. We proceeded to play the first piece, which seemed to me to be quite boring and consisted mostly of counting bars rest. After the continuous involvement that I’d experienced in brass bands, the music seemed incredibly long drawn out. I hadn’t the slightest clue whether anyone could hear what I was playing, and, even worse, the part I had to play was absurdly easy.

There was an interval halfway through the morning and I spotted Mr Neale and went over to him. I was still playing my cornet and he asked me if I could find a trumpet to play. I went home and the following week asked at school if they had a trumpet that I could borrow. As luck would have it, they found a battered old instrument and I gave it a go. I was quite concerned that playing the trumpet would ruin my cornet technique and was determined to segregate the two styles completely.

And so began a routine of travelling to Birstall for orchestra rehearsals every Saturday morning during term time which, although I didn’t know it at the time, would last for the next seven years.

I didn’t really enjoy it much for the first few weeks because the music was too easy and it didn’t really seem to matter whether I was there or not. Just when I was considering giving it all up Mr Neale came to see me and said that I should start going to the Intermediate Orchestra instead.

I gratefully accepted his recommendation and the following Saturday turned up at a different school in Birstall for my first rehearsal with the Intermediates.

My initial impression of being in this new orchestra was that it seemed so vast. The hall was crammed with children in every section. I think there must have been about one hundred and twenty of us. I was introduced to the conductor, a Mr. Hayworth, and also met a boy called Andrew Holland, and we quickly became friends. I was impressed with Andrew because, at thirteen, he was a bit of an old hand and seemed to know all the girls.

I began to notice the girls. I was pretty pubescent at the time and females were beginning to arouse my attention more than they had previously. I began to see possibilities, especially when I hung around with Andrew. His speciality was buying chocolate peanuts and attempting to flick them down the spectacular (as it seemed to me at the time) cleavage of a girl oboe player called Helen. She protested in vain and we spent most of rehearsals laughing, messing about generally, and trying to chat up any girl that would tolerate the pair of us.

The orchestra appeared to me to make a huge disorganised noise. Sometimes this was exciting but often you couldn’t really get much of an impression of the overall sound, only of the instruments nearest to you. I was sitting at about eighth trumpet. The music was mostly straightforward classical works with one or two more modern ones occasionally thrown into the repertoire. If I was to enjoy playing a piece, it had to meet one of three criteria; either I had heard it before; I had a lot to play in it; or the part allowed me to play very loudly.

I remember playing the Karelia Suite in the first category (it was the theme tune to the TV programme ‘This Week’), Holst’s Suite in F in the second, and Malcolm Arnold’s Four Scottish Dances in the last.

After a number of rehearsals I played my first concert with the orchestra on the 19th of December at Longslade School in Birstall (1). An older boy called Andy Smith played the first movement of the Beethoven Piano concerto. My parents had had to buy me my first black blazer for the occasion to go with the dickie bow that I’d used in my band concerts. I don’t remember much of the actual performance but this was probably because I was concentrating so hard on not making a mistake on my first time out.

Chapter Three

1965

The year began and, besides doing all the other things you do as a twelve-year-old, I continued to divide the time devoted to music between the band and the Intermediate Orchestra.

The music in the orchestra became a little more difficult. Although technically it was well within my capability, some parts were written for trumpet in the key of C, A or, even worse, E. This meant that we all had to transpose from our natural key of B flat and this was extremely difficult if you weren’t used to it. The leader of the trumpet section, Steve Lenton, asked me to demonstrate a particular passage to him and to the other trumpet players. I had been waiting for this opportunity for ages because I already knew that I was a good player for my age and wanted to show off (not a good aspect to my character unfortunately!). Most of the other trumpet players hadn’t had the constant exposure to the technical brass band stuff that I had experienced so they were at a relative disadvantage. Unfortunately, although I could have easily managed it in our natural key of Bb I had to transpose this particular piece and made a real mess of it. I was mortified that I had fluffed my big chance in front of everyone and spent the whole bus journey home seething at the injustice of life.

It was about this time that I began to be aware of all the social aspects of being part of the orchestra. I started to make new friends and we all formed groups at break times and swapped gossip. A central theme of the break was the visit to the tuck-shop, where we would scoff Wagon Wheels, Potato Puffs, and other assorted goodies.

Summer came and there was great excitement for me at the news that I was about to go to Colwyn Bay on my first orchestra course. I’d never been away from home before. I didn’t really know what going on a course involved but I’d been told that we were going to stay in a school while we practised for a concert. I discussed it with one of my new friends, a trombone player from Market Harborough called Len Tyler. He was also going and he became my closest friend on the course even though he was a couple of years older than I was.

The big day came and my Dad took me to catch the bus that would take us to the course. The bus took us to Leicester and then onwards to Colwyn Bay. We arrived in the afternoon and were shown a classroom and my first mild surprise was to be handed some collapsible camp beds that we were expected to erect and sleep on. No-one showed me how to put these awkward contraptions together and I had to gawp around stupidly to see how the others did it. Worse still, nearly everyone else seemed to have sleeping bags to go on top of the beds. I hadn’t been warned about bringing one (not that I’d ever seen a sleeping bag before) and I had to make do with a sheet and some blankets, which was decidedly less cool.

So this was my introduction to dormitory life on an orchestra course for the first time. I quickly learned that when there’s a group of you sleeping on camp beds overnight in a classroom, there’s always going to be some fun. This fun consisted of talking, generally messing around, and not going to sleep when the lights were switched off. I learnt some amazing new things. Firstly, some boys smoked! Even more astonishing, I soon realised that some boys were using a deodorant underarm spray called ‘antibo’ (it took me two years to realise that they were talking about anti-b.o. – body odour). I’d never realised such things existed.

But the most vivid memory is the talking and laughing after lights out. Sometimes the talking would last for 20 minutes or so, sometime for a couple of hours. Sometimes there would be silence for a couple of minutes only for someone to fart or make a silly sound which would set us all off in a fit of giggles. The most popular prank consisted of creeping across the dorm in the dark, grabbing the metal sides of the camp bed and tipping the sleeper onto the floor. Nobody escaped having this done to them at some time or other, including me.

Apparently we were allowed to wander out into the town when we were not rehearsing and, on the second day, Len and I walked down to the sea front and around the shops. We entered something I’d never seen before called an amusement arcade and I discovered some electronic games called fruit machines. I was fascinated, and the next day walked down to the town myself and tried them myself. There are no fruit machines in Gumley.

I discovered another remarkable feature of the course – we all had to sing grace before meals. This was very strange to me – particularly since we had to sing something in Latin called ‘Non Nobis Domine’. Worse, we had to sing it in round form two bars behind the girls and nobody ever taught you the words. Somehow you were just expected to pick it up as you went along. I managed to keep a straight face as I attempted to do this, unless I happened to catch the eye of one of my friends, which would inevitably lead to a bout of giggles. This custom turned out to be a feature of every course. We did sing it rather well, mind you, and, on one occasion we even reduced hardened dinner ladies to tears.

On one of my trips into town I bought a cloth badge to stick on the inside of my trumpet case. I’d noticed that a lot of players had similar badges fixed either on the inside or outside of their instrument cases showing the various places that they’d been to on different courses. I decided that I’d put mine on the inside of the case to be a bit more subtle (most unlike me).

We gave two concerts towards the end of the week and then it was all over and we had to come home. On the return journey I couldn’t help but notice that a boy and girl in the seat opposite me were kissing! I’d never seen such a thing before (except at the pictures) and tried not to stare even though I was fascinated by the length of their clinches.

The Autumn term began. Steve Lenton moved up to the Senior Orchestra, some boys left, and I moved up about three places within the section.

Obviously, music wasn’t the only thing that I was involved in at the time. I loved sport, especially athletics and rugby, and had to try and achieve a balance between these and music. Like most brass players however, I think I was always conscious whenever I played in the rougher sports as to how I would play again if I damaged my lips or teeth in any way.

Chapter Four

1966

By the turn of the year, I was among five children from the school orchestra who were being picked up by bus from Market Harborough to travel to County Orchestra rehearsals every Saturday morning. Apart from me, they were Len (trombone), Veronica (flute), Kathryn (violin) and Valerie (clarinet). If my Dad couldn’t take me to rehearsals for any reason I would cycle the five miles to the pick up point with my trumpet case strapped precariously to the handlebars on my bike.

These rehearsals continued throughout the spring and I made new friends. I slowly managed to adapt my cornet and trumpet playing technique so that I could utilise the appropriate style when necessary, avoiding a vibrato tone on the trumpet at all costs. I learnt to master the transposition to the key of C, but the other keys were much more difficult.

————-

Our summer orchestra course this year was to be at Lowestoft. The arrangements followed the usual pattern of coach trips, arrival at the school, allocation to dormitories, and so on. The combination of a seaside town, sunshine and plenty of free time meant it was more of a giant holiday than an orchestra course. But the teachers still made us rehearse rigorously. We played two works that featured among my favourites – Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony and Smetana’s Vltava.

I gradually became aware of a number of different aspects to the course itself, and to the way that the rehearsal sessions worked.

The course consisted of communal breakfast in the main dining room followed by morning rehearsal. We practised all the way to lunchtime and, after the meal, were allowed to take the afternoons off as free time. We could do whatever we liked during this period. Some people preferred just to hang around the dorms but most of us would take ourselves off into the town in little groups. We had to return for the evening meal, which was usually served at 5:30 or 6:00. There then followed a shorter evening rehearsal until 7:30 or so, after which we were free to amuse ourselves.

Lights out was nominally at 10:00 or so, but we often switched them on again as soon as the staff were out of sight. They would catch us out of course and threaten dire consequences if we didn’t go to sleep. At this point we usually reverted to torches or talked in the semi-darkness.

As far as the rehearsals themselves were concerned, a few things stick in my mind. Firstly, during the breaks, there were always kids that insisted on playing all the percussion instruments, or any instrument but their own. This really got on my nerves as it invariably resulted in a loud horrible noise that didn’t do anything for anyone. They all wanted to bang drums as if it were clever or something; I was very thankful that I wasn’t a percussionist – I would have hated people messing with the kit.

Secondly, the sheet music folders always seemed to be in a mess. The problem was that no-one appeared to take responsibility or ownership of the folder for each section. So you invariably had occasions when we couldn’t find the music or the whole folder itself. It was always worse when the orchestra started playing a piece and we were still searching frantically though all the music in the folder trying to find the correct part. I lost count of the times when I had to play the first entry from memory while one of us scrabbled through all the sheets of paper.

The course itself was very enjoyable and although I was still rather shy with girls, I’d pal around with Andrew Holland and one or two others which at least allowed me the odd conversational opportunity with the opposite sex. The week itself culminated in two concerts – in Beccles on the 20th of August, and in Lowestoft itself on 22nd (2).

The main problem with these concerts was that they were both in churches. This was really awkward because of the size of the orchestra and it inevitably meant that the brass sections would end up occupying the choir stalls. There was never enough room on these benches and we couldn’t hold our instruments properly – never mind get the music stands right.

I had a number of friends in the orchestra by this time and we would hang around together or walk down to the beach in small groups. I became friendlier with Veronica and we bought each other identity bracelets (they were very fashionable at that time).

One of the traditions of our orchestra tours and courses was that we played a concert in Leicestershire immediately on our return. Accordingly, the day after we returned from Lowestoft we were in action at Guthlaxton Grammar School in Wigston (3). David Pugsley, a Senior Orchestra clarinettist, played the Weber Concertino.

At the start of the Autumn term I was promoted to lead the trumpet section. Even though I was proud to take on the role, I still felt that it was a lot less demanding than playing solo cornet in the band. However, being the orchestral leader meant that I had to play any solo-marked passages, and so gave me some extra responsibilities and involvement with the music.

Mr Haworth acknowledged my place in the orchestra by giving me a red badge. I’d previously noticed when travelling on the bus that a badge scheme existed right through the three orchestras. I’d asked about it and been told that each badge denoted which orchestra that you belonged to; yellow for Junior, red for Intermediates, and blue for Seniors. There didn’t seem to be any formal route to acquiring such a badge but I was very grateful and proud that I’d received mine.

Mr Haworth himself was a very popular figure. He brought a sense of humour to his conducting and managed to strike the right balance between treating us as grown ups as far as the demands of the music were concerned whilst taking account of our tender years. He would single out various players and refer to them as famous musicians of yesteryear. The percussionist was always called Gene Kruper even though none of us had ever heard of someone who went by this name. If he held up his baton and failed to get quiet from the players he’d say “I’m not holding this stick in the air for somebody to hang a lamp on”.

On the 14th October and before our next course, we repeated the Guthlaxton program at Syston Methodist Church (3), again with Dave Pugsley as the soloist.

At the end of the month we went to Cambridge for a short concert tour. We all stayed with hosts this time instead of schools and I shared a room with a boy called Stephen Pepper, who played the bassoon. The room had a record player in it and I remember it being the first time that I had ever seen one! Stephen and I went through the record collection and ended up playing Ruby Tuesday by The Rolling Stones over and over again. I can’t remember anything else of significance concerning the visit except that we gave two schools concerts and eventually returned home after four days away.

On our return we played much the same program as in Cambridge in a concert at Oakham (2).

Next month I had my first taste of being asked to play as a ‘freelancer’. I was invited to play in the small pit band at the Phoenix Theatre in the Happiest Days of Your Life. I received a small fee for my efforts. It was the first time that I had realised that you could earn money through playing a musical instrument. Nobody had told me that before!

Our last Intermediate concert of the year was at Birstall on the 21st December. We used the occasion to vary the format of our concert program somewhat and we gave a number of players the opportunity to perform individually or in quartets (4). Marion Shaw, Richard Anderson, Clive Aucott and Robert Heard were the soloists in the Vivaldi concerto for four violins; Marion Shaw, Susan Phipps, Vanessa Hood and Jane Monk were soloists in the Salon Suite; Nicola Swann played the Haydn Oboe Concerto; Stephen Pepper the Capel Bond Bassoon Concerto; and Andy Mack the Weber Clarinet Concertino.

Lambert Wilson and Bert Neale

Chapter Five

1967

I obviously had another life outside the band and the orchestra, and, even though I was part of so many musical activities, I still had time to do some of the normal things that kids did at that age. Living in the country, I had to help out on the local farm, but even these chores didn’t stop me getting up to the usual sorts of mischief with my pals, such as scrumping and birds’ egg collecting.

I also had my friends at school and, like most of my classmates, I was also becoming more interested in girls. Make that very interested.

————-

During the Spring half term I travelled with the orchestra to play in Wisbech (5) and Cambridge (6), (7) on the 13th and 14th of February. The second concert was a rather unusual double program. It consisted of a morning concert – where Nicola Swann played the Haydn Oboe Concerto – and an afternoon concert where Andy Mack repeated his previous day’s performance of the Weber Concertino. The two conductors on this occasion were John Westcombe and Jim Haworth.

Shortly after Easter, on the 30th April, the orchestra gave a concert at St Peter’s Church in Church Langton (8), where Sue Phipps played Robert Valentine’s Flute Concerto, the first performance of this work since the eighteenth century. The Mozart Violin Concerto soloist was Stuart Johnson, and John Adams played the solo cello in the Baumann work. This was a rather special occasion for me for two reasons. Firstly, I had been to junior school in Church Langton just a few yards away from the church and knew the area well. Secondly, because it was local, for the first time my parents had come to the concert to hear us play.

As part of the Leicestershire Schools Music festival, we repeated the concert at Castle Donington Secondary School (8). Just before this I’d been asked to be part of yet another musical organisation – the ‘Area Orchestra’. This consisted of orchestras from schools in the south of Leicestershire. In my view this was an entirely superfluous venture and, although I went along to the rehearsals in Lutterworth, it just took up even more of the precious little free time that I had after school each day.

Back at school, I was getting fed up with having to play in school assemblies. This meant that I had to be separated from my mates, and miss out on the laughs and larking around. It was also embarrassing given the quality of the School Orchestra. But I had also taken quite a fancy to a certain woodwind player, one of the small group of us who went to the County Orchestra from Market Harborough. We used to mess about in the small musical storeroom behind one of the main classrooms. Along with other pupils that were in the School Orchestra, we used to try and play one of the many spare instruments that were lying about on the shelves. My speciality was playing the hornpipe on the tuba as fast as I could.

I was fifteen in May and had never really gone out properly with a girl before, and was waiting for the right opportunity.

The summer school holidays arrived and I couldn’t wait for the day when we would be off on our next orchestra course. This year it was to be held at Southport. The week of rehearsals culminated in a concert at the Holy Trinity Church in Southport on the 1st August (9).

We were based in a large school as usual. There were about a dozen or so of us in each classroom dormitory and we got up to all the usual pranks. One of the favourite ones was to loosen all the legs of someone’s camp bed so that it just stayed up but immediately collapsed as soon as you sat or lay on it. We would also carefully carry people who were fast asleep on their beds outside to spend the night in the open air. What they thought when they woke up I don’t know.

The worst prank that we got up to was when a number of us ‘bounced’ a female member of staff’s car so that it ended up in a playing field adjacent to the car park. That wouldn’t have been so bad except for the final resting position – lengthways between two goalposts with only a few inches to spare at either end. In hindsight this was a wicked thing to do but it seemed hilarious when you were 15 years old.

Half the boys were involved in trying to make new relationships with the opposite sex (and the half that weren’t were wimps in my immature view!). In reality we were a bit too young to get up to anything completely overt, but that didn’t stop us pretending. I flirted with a flute player but didn’t really achieve anything except to chat to her during our daily walk down to the sea front. A whole group of us used to go together, and generally fool around trying to impress our peers – as kids do at that age.

What was especially exciting for a youth of my tender years was that the girls seemed to be in some sort of perpetual contest as to who could wear the shortest mini-skirt. How they got away with some of them I’ll never know, but there were definitely no complaints from me personally.

Eventually, we made our way back from the course and after the bus had dropped most people off at Leicester, we journeyed on to Market Harborough. Somehow or other Miss Woodwind and I got into a ‘staring contest’ (very mature, I don’t think). Anyway, one thing led to another after that and she and I started to spend more time with each other in a kind of unspoken arrangement, although we weren’t really going out together.

As soon as we returned we played a concert at Bushloe High School in Wigston (10). Among other items, Rob Walker from the Senior Orchestra played Weber’s Hungarian Rondo for Bassoon, and Susan Phipps played the Dittersdorf Flute Concerto. Included in the same concert was William Mathias’s Sinfonietta, which was specially commissioned for that year’s Leicester Schools Festival of Music. The festival had been inaugurated in 1965 and the intention was that it would be held every two years.

I returned to school in September as a fourth former. Although this academic would be my ‘O levels’ exam year, I was still playing with the School Orchestra after the end of lessons, with the band on two evenings a week, and with the Area and County Orchestras in the rest of my spare time.

On top of all this, I had joined a jazz group. A few months earlier, a clarinettist in the school orchestra, a boy called Brian Downes, had suggested that a few of us form a small trad jazz group. I agreed, together with a trombone player called Glenn Pollard (my friend from the early days of the town band) and a pianist called Steve Webb. The four of us rehearsed and started to sound reasonably good. Brian supplied all the music and was the real star because he could play jazz very well. My jazz style was pretty awful since I had always learned to play ‘straight’.

But we soon started to get bookings to play at various functions, including local clubs and night-spots. Brian told us that we were to audition for Opportunity Knocks on the following week. So a few days later we went to Nottingham and were one of about two hundred acts taking part. We made the last twenty-five before being knocked out. I felt that what we needed was a drummer, otherwise, as none of us were older than sixteen, I thought we might have made it to the final.

————-

We had only just started Saturday morning rehearsals for the new term when we were asked to give a concert at the Beauchamp Grammar School on the 13th October. Richard Fairhead played the Mozart Piano Concerto Number 9 (10).

A few days later, I had my first call to rehearse with the Senior Orchestra. I didn’t seem to go through any formal promotion process like the other players. One day, during an Intermediate rehearsal, one of the staff said I was wanted in the Longslade Upper School. To this day I don’t know why, I only remember the feeling of terror as, clutching my trumpet case, I made my way along the footpath between the schools.

I arrived at the Upper School and just stood around. Eventually, Steve Lenton spotted me and told me to sit at the end of the trumpet section. I remember Steve was leader, Colin Clague was second and one or two others were in between him and me. I was totally overawed by the whole atmosphere because, unlike the Intermediates, the Senior brass section sat on a stage above the main body of the orchestra, and, as a result, the whole dimension of the orchestra seemed different. Everyone was much older than me and appeared to be very sophisticated and grown-up. Then I noticed that Jimmy Watson was in the trumpet section! I was shocked! Jimmy was the champion cornet player in the UK and must easily have been the greatest youth trumpet player in England. The realization that I would be playing alongside him but never be his equal in ability brought me down to earth with a bump.

I quickly learned a number of facts about being in the Senior Orchestra.

Firstly, the older boys had power and the younger ones didn’t. Younger ones such as myself did as we were told otherwise we were threatened with all sorts of punishments. Funnily enough, these threats rarely seemed to be carried out. So there was no bullying as such; it was more the implicit threat of being bullied that maintained the status quo.

I was always being threatened with the ‘pissoir’. It took me ages to work out that the pissoir was the men’s urinal and the threat meant that if you didn’t behave you would end up getting dunked in it while it was flushing. Fortunately, I managed to avoid this experience but I know of one or two others who weren’t so lucky.

Secondly, virtually every boy smoked cigarettes. You almost had to in order to look cool. So at break time we all cleared off to have crafty fags. I soon got into the swing of this and remembered to buy my ten Conquest cigarettes every Saturday while I was waiting at the bus stop in Market Harborough.

Thirdly, the orchestra took things a bit more seriously than we had done in the Intermediates. The quality of playing and the whole sound of the orchestra was completely different. Because everyone was that much older, there was none of the running around and giggling that was part of the Intermediate set-up.

Another important issue for me was that there was a whole new orchestra of girls to study closely and evaluate individually. While we were counting bars rest it was incumbent on me to methodically check out each female and award them a mental rating (adolescent boys do this, you know). Even though most of the girls were older than I was and therefore unattainable, I was struck immediately by how many attractive girls we had playing in the orchestra.

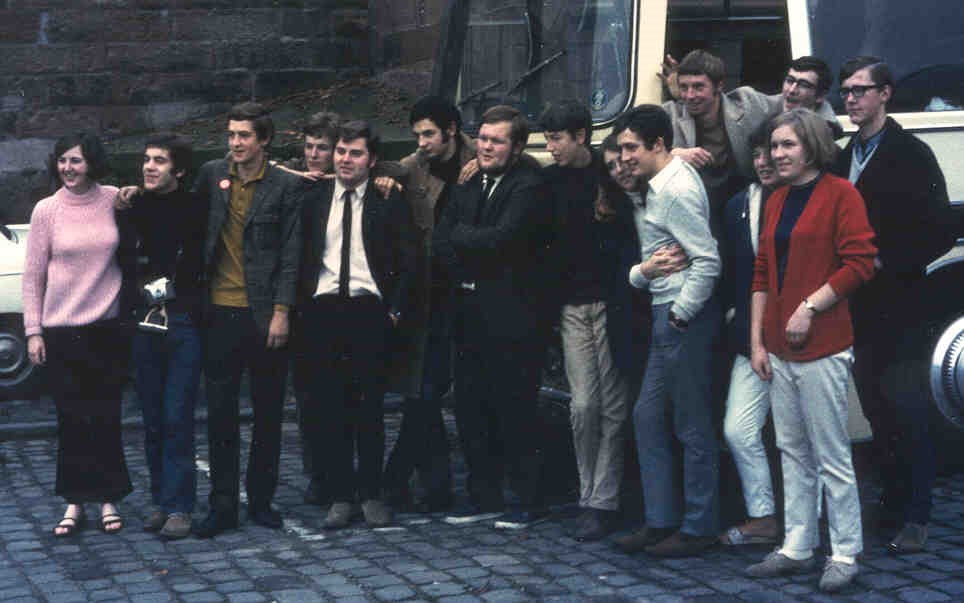

Although by now I was rehearsing with the Seniors, at the end of October I was among a number of senior players who were asked to go on a course with the Intermediate orchestra. It was to be my first trip outside England – to Ballymena in Northern Ireland. We all looked forward to it tremendously – especially me – because it would finally mark the proper beginning of my relationship with Miss Woodwind.

Altogether there were seventy-eight girls and boys and six staff going on the course. They were (in no particular order):

Linda Coe, Joyce Fraser, Hilary Orton, Ann Smith, Malcolm Bennett, Richard Harris, John Smith, Martin Walker, Veronica Adcock, Valerie Blissett, Kathryn Clewlow, Corinne Bradley, Elizabeth Salem, Richard Errington, Stephen Hopkins, Stephen Hunt, Jonathan Salem, David Stevens, Mary Greenhow, Andrew Barnwell, Helen Parker, Susan Phipps, Kathryn Marcer, Stephen Lenton, David Matthews, Graham Pyatt, Christine Wells, Robert Heard, Peter Lawrence, David Thompson, Helen Barksby, Rosalind Burton, Eleanor Cooke, Vanessa Hood, Vanessa Knapp, Heather Milbank, Jacqueline Spiby, Andrew Mack, David Sharp, Jeffrey Zorko, Kathryn Halsall, Lynn Mace, James Eccles, James Shenton, Lisbeth Ward, Jane Sanders, Clive Aucott, Richard Fairhead, Lorraine Aucott, Sarah Brookman, Julia Shoulder, Anne Sim, Alison Tilsley, Neil Marner, Paul Jarvis, Barbara Allen, Gillian Allen, Barbara Bath, Lynne Faulks, Sheila Smith, Sandra Taylor, John Adams, Barry Belcher, Stephen Draycott, Andrew Smith, David Smith, Diana Birks, Barbara Cooper, Catherine Jinks, Patricia Kelly, Helena Kendall, Elizabeth Mackay, Penelope Roberts, Frances Stedman, Glyn Belcher, Stephen Gee, Charles Jones and me. The six staff were Messrs Hallam, Matson, Robb and Pinkett, Miss Chandler and Miss Yorath.

The bus journey was going to be very special for me. I had finally plucked up the nerve to ask Miss Woodwind if she would sit with me on the bus and I was determined that I’d have my first snog with her. We’d only been travelling a few minutes when I tried the first kiss. She said I was awful. Ah well, I thought, I could only get better and practised all the way to the ferry.

The ferry was a great adventure for me because I’d never even seen one before let alone sailed on one. We duly arrived in Belfast and then travelled on by bus to Ballymena. When we arrived we were all allocated to ‘hosts’ who would look after us for the week. I was disappointed to find that although I’d be staying at a very posh house it would be with a girl (whose name I won’t mention) who was only about thirteen, and another boring wimp-type boy about my own age.

Each day we were taken by our hosts to the local school where we practised or, more often than not, were whisked off by bus to take part in concerts at various local schools.

Whenever we went away on these orchestra courses the staff would organise some sort of sightseeing trip and this time was no exception. We were taken to the Giant’s Causeway and allowed to clamber around on the uniquely shaped stepping stones.

The week consisted of nine concerts:

22nd – Lambeg (11)

23rd – Bushmills Grammar School (schools concert a.m., public p.m.)

24th – Carrickfergus (schools concert a.m., public p.m.)

25th – Magherafelt (schools concert a.m., public p.m.)

26th – Ballymena

27th – Rathcoole

Andy Mack played the clarinet concertos and Richard Fairhead the piano concertos. The program was broadly the same on each occasion.

During the course I was determined to see Miss Woodwind. She was staying with another girl who was friendly with one of my pals. One evening my friend and I met up to walk to the house where they were staying, even though it was some distance away from our own. We managed to spend a couple of hours with them because their hosts were out for the evening. Unfortunately, their hosts discovered our liaison and weren’t impressed. They complained to Eric and he took both Miss W and her friend aside to let them know that he was not amused, and any repetition of their behaviour would result in them being sent home.

Before the course ended I had made a number of new friends. For the first time I met two boys who were to become firm friends for many years to come – Dave Smith and Steve Draycott.

We returned from Ireland and started school again after the half term. Miss Woodwind and I started to go out ‘properly’ and our first date involved going to the cinema together. My parents had allowed me to go and a local lad in our village had a girlfriend who also lived nearby which meant that he could give me a lift home afterwards. I was so excited I don’t remember much about that first date but I think it was reasonably successful as we soon started going to the cinema regularly on a Saturday evening.

————-

By now I was principal cornet with the Market Harborough Town Band. The band still weren’t very good but I stuck at my practice and enjoyed being leader of the band at fifteen. I continued to take part in a number of solo contests with some mixed success.

On the 10th November I played my first concert with the Senior Orchestra at Ivanhoe College in Ashby (12). The soloists for the Oboe and Violin Concertos were Philippa Elloway and David Matthews respectively. It was a thrilling occasion for me and an entirely different matter to the previous Intermediate concerts. It wasn’t just the higher standard of play, but the whole atmosphere seemed more serious and professional. I enjoyed it thoroughly even though I felt that I was only a very small part of the whole enterprise.

————-

I think it’s easy to forget now about other aspects of that era which stick firmly in the mind of those of us who were around in the sixties. It wasn’t just the music, but the social upheaval and sexual freedom that began to emerge at that time. I particularly remember the advent of the contraceptive pill and the excitement for us all at the time of the prospect of sex without the usual encumbrances and worries.

Pop music was all around us as anyone my age will tell you. The clothes were another symbol of the times. Apart from the mini-skirts, flower power and influences from America had contrived to completely change everyone’s wardrobe. My mum had made me an orange flowered shirt with a penny collar, and another in purple silk.

The latter I would proudly wear with my purple corduroy jeans and purple corduroy jacket!

I had crimplene long-sleeved shirts, tie-dye sleeveless ones, cotton ones with black lace-up necks, hipsters instead of trousers, and, most of all, waistcoats. Wearing waistcoats without any coat was somehow significant because waistcoats were originally designed to be worn as part of a suit and I think the symbolism was unmistakable. As well as the minis, girls wore hot-pants, maxis, jeans, smocks, fluffy jumpers and see-through tops. Unfortunately, they also wore tights.

————-

The orchestral diary for 1967 drew to a close with extra rehearsals at Birstall during the Christmas holidays.

THE BRIANDROS COMBO

(Glenn Pollard, Brian Downes, Yours Truly, and Steve Webb seated)

THE SCHOOL ORCHESTRA

(Glenn Pollard, Len Tyler, Ian Hardcastle, Geoff French and mini-me next Diane Henderson)

and other non-brass players whose names I don’t remember (sorry)!

1968

From late 1967 to early 1968 I was often involved with both the Intermediates and Senior Orchestras. A number of us who had recently moved to the Seniors were sometimes brought back for engagements with the Intermediates while our replacements were gaining experience.

I think Eric Pinkett began to formally acknowledge me as a player at about this time. Obviously I’d been aware of Eric from my early days in the Intermediates when someone had pointed him out to me. But I’d never been in an orchestra that had been conducted by him before and, until someone pointed it out to me, I didn’t quite understand that he was the driving force behind the whole organisation. It was remarkable that he managed to make time for so many young musicians and understand their strengths and capabilities. If one thinks about the hundreds of children who passed through the various orchestras over the years, it would have been hard enough to remember their faces let alone their relative ability.

On January 2nd I was with the Seniors when we were filmed during rehearsal by the BBC as part of the Music International program to be shown on BBC2. This was an exciting new venture for me. We were at Birstall as usual but the main hall was packed with huge lights and cameras. We had to play naturally and pretend to ignore the intrusion of all the equipment. I’m sure we all looked far more serious than we usually did. Eric had to have make-up applied to his shiny head and we all attempted to brush our hair and look our best, knowing that our parents and friends would eventually be seeing us on TV. The film crew recorded us playing Nimrod, Candide and Tippett’s Suite in D conducted by Sir Michael.

The spring term began. Occasionally we would give a concert during term-time and one of these took place in the half-term in the Temple Speech Room at Rugby School on the 27th February (13). Dave Matthews played the Bruch Violin Concerto, but the concert was more memorable for our first public attempt to play the fiendishly difficult Walton Partita. Perhaps even more importantly Norman Del Mar was in the audience to listen to us – no doubt with the summer’s Vienna tour in mind.

I still hadn’t entirely lost touch with the Intermediate Orchestra and helped them out at their next concert on the 10th of April at Stamford (14).

I used to love going to rehearsals in those days. It was such a marvellous hobby as well as tremendous fun. The combination of music, girls, larking around and practical jokes was a heady mixture. Every Saturday, I would catch up with my friends, male and female, and swap news. There would be new music to learn and, occasionally, new faces arriving. There was excitement when Eric announced the next new project, particularly if the news involved a TV session, a recording, or a course away from home. My schoolwork suffered because everything else seemed to pale by comparison to my involvement in the orchestra.

The players at about this time were:

First Violin Cello Bassoon

David Matthews Kim Punshon Robert Walker

Andrea Sharpe Anthony Lewis Maurice Turlington

Judith Allen Julie Houlton David Smith

Julia Shoulder Fiona Torrance Stephen Pepper

Stephen Whetstone Ian Heard

Michael Savidge Graham Stevenson Contra-Bassoon

Mary Turner Vivienne Shorthouse Maurice Turlington

Carol Leader John Adams

Robert Heard Barbara Bath Horn

Vida Schepens Diana Birks Thomas Lewis

Marion Davis Lyn Eyre David Thompson

Margaret Smith Christine Posnett David Stevens

Margaret Sharpe Sandra Roberts Catherine Wortley

Anne Jameson Julia Mobbs Dianne Phillips

Heather Walker Elizabeth Marlow

Susan Aiers Elizabeth Salem Trumpet

Anne Webster Stephen Lenton

Alison Tilsley Double Bass James Watson

Sybil Olive John Smith David Hoffler

David Vercoe Trevor Nurse Philip Monk

Eleanor Cooke Ruth Hopkinson

Kathryn Clewlow Elaine Harrison Trombone

Linda Brice Pamela Maddock Roger Harvey

Paula Marlow John Turner

Second Violin Hilary Orton Martin Slipp

Richard Anderson Lynda Coe John Davis

Elizabeth Deans David Sharp

Jane Hyman Piccolo Richard Fairhead

Kathryn Hopper Sheila Angrave

Robert Grewcock Tuba

David Abbott Flute John Smith

John Whitmore Ruth Webb

Janet Crawshaw Sheila Angrave Timpani

Rosemary Carr Hilary Ball Andrew Smith

Clive Aucott Susan Phipps

James Shenton

Paul Jarvis

Second Violin Oboe Percussion

Judith Proctor Philippa Elloway Margaret Whiteley

Lynn Mace Kathryn Vernon Stephen Whittaker

Stephen Gee Karen Griffiths Wendy Wilson

Anne Wright Nicola Swann Celia Mulgan

Ruth Storer

Viola Elizabeth Mackay Harp

Moira Watkinson Pamela Wright

Helen Leech Cor Anglais

Susan Taylor Nicola Swann Piano

Alice Freshwater Richard Fairhead

Ian Anderson Clarinet

Rona Eastwood David Pugsley

Malcolm Dicks Rosalind Lenton

Graham Parker Robert Oldham

Toni Smith Susan Underwood

Lynne Faulks Andrew Mack

Kathryn Marcer Jane Monk

Benedict Mason Valerie Blissett

Glyn Belcher

Stephen Draycott

The Easter course this year was to be held in Chippenham. This was my first taste of being on a course with the Seniors. Miss Woodwind and I had moved up to the Senior Orchestra at about the same time and I knew we would be able to develop our friendship while we were away.

The course was an altogether different affair from my previous Intermediate courses. I had previously realised that several of the senior boys formed a close circle that was tacitly acknowledged as the ‘in-crowd’. A sense of adventure, general bad behaviour and pseudo-adult pastimes marked them out from the boys who tended to behave themselves. Some of the in-crowd names that spring to mind were Ian Heard, Dave Pugsley, Robert Walker, John Smith, Dave Mathews, Andy Smith, Jimmy Watson, and Tony Lewis. There were no doubt others whom I may have omitted but there were no absolute criteria and some were more ’in’ than others were. I decided from the start that although the in-crowd boys were older than I was, I was going to try my best to try and hang around with them.

I managed to get a space in the corner of the ‘in-crowd’ dorm. This was an exceptionally daring thing for me to do because I was definitely not ‘in’. You had to be accepted into the group before you stay in their dorm and there was no way that I had been accepted or even hardly acknowledged. One or two of the others questioned my right to be there but I managed to hold out by claiming that the other dorms were full.

I quickly got used to the most important aspect of any course – the drinking. We all went out each night and knocked back as much beer as possible with the objective of becoming completely drunk. How we managed to get served at that age I don’t know. We would make our way back from the pub in a completely inebriated state, falling over, being sick, doing utterly stupid things, or a combination of all three.

During our drinking trips in the pub we became aware of some of the local yobbos and we heard that they didn’t like us and were spoiling for a fight. One night some of ‘our girls’ were insulted by some of these local youths and, worse still, they had actually hit some of the junior boys. We were incensed and from somewhere (and I’ll never know how) we armed ourselves with baseball bats, cricket stumps, and assorted weapons and went charging off around the playing fields determined to remove the threat. Thank God we didn’t find them or we would have been in serious trouble.

On the third night we had a seance. Apparently, this was quite a regular feature of a Senior Orchestra course. About half a dozen of us sat around a table and each had a finger on an upturned drinking glass. We used to turn all the lights out and ask questions and the glass used to move in response. I was never quite sure whether someone was doing this deliberately or not. I remember once the glass spelled out to us that John Smith’s tuba had been moved from one side of the rehearsal hall to the other and we all dashed downstairs to see if this was true. It was! John swore that it he’d left it on the opposite side of the hall. Of course, I never knew whether someone was taking the mickey and, if so, how many of them were in on it. The majority seemed to believe it and it seemed to work regardless of who comprised the group. Mind you, we had at least as many failures as successes – giggling often spoiling the supposedly occult atmosphere.

The one thing I can’t explain is the ‘dead boy’ ceremony. This involved someone laying with their eyes closed on a table in the semi-dark. Six of us stood round the table and each put one finger under the boy, one at each shoulder, one either side of the hips and one at each calf. We would then chant…’he looks dead’…pause…’he feels dead’….pause…’he is dead’. We all then tried to lift him up. The first time we did it I was totally shocked and amazed. I was one of those who had a finger underneath the boy; he seemed to weigh nothing and shot up about four feet into the air. There were gasps from everybody and we had to lower him quickly back to the table.

I couldn’t explain it. There didn’t seem to be any weight to him at all; how could that be? Why didn’t he fold up in the middle? He stayed as straight as an ironing board.

We repeated the experiment many times on other nights and other courses. It didn’t always work; sometimes someone got the giggles or didn’t lift properly. But, inexplicably, it often did.

I had realised before the course that one of the days that we were away coincided with an important contest for the band. After much discussion, the band agreed with me that I should go on the course and that they would come and fetch me on the Saturday to take part in the contest and bring me back afterwards. When the day came a chap called Geoff Orange picked me up in his car and brought me all the way back from Chippenham to Market Harborough. I got changed and we all went off in the band bus to Lutterworth where the contest was being held.

When we arrived there didn’t seem to be much activity. Geoff got out of the bus and asked the first person he met if this was the correct venue. The person replied that it was. When Geoff asked if he knew about the brass band contest, the person said yes – it was due to take place on the following Saturday!

The band were stunned. What a farce. Geoff had got the dates wrong and we had come all that way for nothing. But it was much worse for me since I had come all the way back from Chippenham. Geoff had to take me back afterwards and I had to answer numerous questions from everyone about how had we got on. It was so embarrassing to have to explain everything.

During these courses the girls had their own way of fooling around (so I’m told). This often involved raids on the school canteen and subsequent midnight feasts by torchlight. On one occasion they stuffed pillows under blankets to cover the absence of a certain oboe player as she disappeared for a late night tryst with a clarinettist. On another they took someone who was fast asleep out of the dorm in their sleeping bag to spend a night in the corridor. Although the staff were supposed to take a tough line over such behaviour, nobody seemed to get into serious trouble although the teachers must have known what was going on.

The teachers associated with the Senior Orchestra were somewhat different to those involved with the Intermediates. Apart from Eric and Jack Smith, there were a variety of others called in to help, organise and control us all. One of the favourites who we would take the mickey out of was Johnny Westcombe. Mr Westcombe always tried to look cool. He was famous for wearing his shirt or jacket collar up thinking that it was trendy. One day about twenty of us walked into rehearsal all with our collars up. I couldn’t play for laughing when I saw the expression on his face.

Generally though, the teachers (including Mr Westcombe!) were great. They helped us enormously and most of them were willing to share the laughter and enjoy themselves. They would often bring their golf clubs with them on these residential courses and take the opportunity to have a game if time allowed.

During the course I was surprised to notice that not only did we have Jack Smith as an organiser and the other musical teaching staff, but we also had a teacher to repair and maintain instruments (often by commandeering the school woodwork room). Jack himself had a particular affinity with many of us. He always seemed to be at the centre of everything as someone we could talk to if we had a problem and who would take care of all the administrative details. He became a permanent feature of every course and must have put an enormous amount of effort into organising matters behind the scenes.

I think the main reason that we respected the staff was that they used to have to put up with the same awful food and conditions that we did. But it didn’t end there. Even guest conductors often had to share dorms with the teaching staff (although they were sometimes fussed over by some of the girls who would bring them breakfast in bed).

One day I walked into the main hall to find a dozen or so players sitting on the stage and singing a Beach Boys hit, acapella-style. I was knocked out at the great sound that they managed to produce based on their natural grasp of harmony and range of voices. I would have loved to have been old enough to join in. It was only at this point that I realised that so many of our players were such talented singers.

Back to the music. Sir Michael Tippett conducted the Ritual Dances from his opera ‘A Midsummer Marriage’ for a new film called ‘Music!’. (A few weeks later, on May 25th, a BBC sound crew came to our Saturday morning rehearsal at Longslade to record the sound track to go with this film). Normal Del Mar also came to conduct us during the course, along with two specialist tutors – Trevor Williams (Leader, BBC Symphony Orchestra), and Ambrose Gaultlett (Cello professor at the Royal Academy of Music).

A short comment on Michael Tippett: Sir Michael first became involved with the CSM in 1965 when he agreed to take part in the Schools Festival and conduct two major concerts at the De Montfort Hall. The logistical problems in actually rehearsing the LSSO for the festival were largely overcome by the orchestra travelling down to Corsham, close to Sir Michael’s home, and taking up residence in a local school for a full week during the Easter holidays.

This enabled Sir Michael to work with the orchestra after his usual days’ schedule. In this way his routine was not disrupted, but perhaps more importantly, from an LSSO perspective, there was substantial rehearsal time for the players and Sir Michael to get to know each other and improve the overall standard of performance.

After a very successful and eventful experience for me we returned home after the Easter break in time for the start of the summer term.

————-

The following month it was my sixteenth birthday and my Dad bought me a small motorbike. This was a marvellous present for me because it gave me new freedom to travel and allowed me to see Miss Woodwind when I wanted to. Once I’d got the hang of riding it I even dared to go to one or two Saturday morning orchestra rehearsals on it.

————-

On May 1st the Senior Orchestra gave a concert in the De Montfort Hall in Leicester (15). Eric had previously decided that we should form an association with an outstanding young English pianist called Nicola Gebolys. She was the soloist on this occasion and joined us in many more performances on our tours abroad.

————-

On the 5th and 6th of June, the Grammar School put on a play called Noye’s Flood. I had to take part, as did most of the School Orchestra. I thought it was embarrassing because playing in the School Orchestra didn’t compare well with playing for the LSSO. How awful to think that I had become such an elitist musical snob at such a tender age.

————-

I was still playing almost every week in the jazz group. I remember one particular occasion when Brian had booked us to play at Lutterworth Working Mens Club (Broadway here we come!). We waited behind the curtain to be introduced to the audience, and the compere turned round and said:

‘Right, lads, on you go. What was the name again?’

‘The Briandros Combo’ replied Brian. Glenn and I exchanged our usual look of exasperation.

‘The what?’, said the compere.

‘The Briandros Combo’, repeated Brian.

‘The Brian what?’ said the compere.

‘The Briandros Combo’, said Brian

The curtains flew open; the compere stepped forward and said:

‘Welcome to four special youngsters, here to play jazz for you this evening. Give a big hand for…. The Tigers!’

————-

Two weeks later I had to go through the annual embarrassing ritual of playing in the Market Harborough carnival procession. It was a terrible ordeal for me as my schoolmates would be there and severely take the mickey because of the uniform and the fact that I was marching. I always wore dark glasses to try and disguise myself but they still spotted me and shouted insults from the pavement while doing impressions of marching German soldiers. Mind you, it didn’t help when one of our trombone players dropped his music. By the time he had run back to retrieve it, it had been run over by the Carnival Queen lorry.

About this time Miss Woodwind and I were going through a bad patch. This was entirely my fault through being immature and stupid (a habit I haven’t entirely grown out of), and we soon broke up. I knew she would be going away to college after the summer holidays and it would have been difficult to maintain our relationship anyway. But it still didn’t excuse the fact that I’d behaved badly.

One of the things that didn’t help was the appearance at one Saturday morning rehearsal of a new double-base player. I don’t know what the other boys thought but she seemed to me to be the most gorgeous thing I’d ever seen – great figure, pretty, long blonde hair, the works. My eyes were on stalks. Her name was Trudy. A few weeks later a rumour circulated to Miss Woodwind that I was going out with her (probably because I never stopped gawping at her). It wasn’t true (I should have been so lucky), but it didn’t help matters.

On 28th June the School Orchestra felt brave enough to play a concert in their own right at the Grammar School. This sort of thing always amazed me. I couldn’t understand how anyone in his or her right mind could stand to listen to such an awful row, let alone pay for it (there’s that musical snobbery again).

The Senior Orchestra continued to rehearse every Saturday and Sir Michael Tippett came up to take us through our paces before our next London concert. We had mixed feelings about Michael’s conducting. While we respected his musicianship, his conducting didn’t seem altogether with it. This may have been partly due to his age and to the fact that his eyesight wasn’t all that good (he suffered from cataracts for some years). Unfortunately, this meant that he often couldn’t quite make out where each section was. He’d therefore cue the trumpets and look for us in the wrong area of the orchestra, which was a bit disconcerting (no pun intended).

Eventually, on July 13th this rehearsal activity culminated in an important concert at the Guildhall as part of the City of London Festival (16). Sir Michael Tippett conducted the whole of the program apart from Walton’s Partita – for which Eric took the baton.

The Intermediate Orchestra’s course this year was at Cromer from July 19th – 27th. Although I was in the Senior Orchestra, a few of us were brought back from time to time to reinforce some of the Intermediate sections and, when asked, I willingly volunteered.

During the course I met a very young violin player called Maureen. Although she was much younger than I was (thirteen) she looked very grown up (so I thought) and had a figure to match. We soon began spending a lot of our time together. Our favourite pastime was sitting on the pier and putting money into the jukebox so that it would play ‘Young Girl’ by Gary Puckett and the Union Gap over and over again. We would then discuss endlessly the difference between our ages, because I was so ‘old’.

We got up to the usual antics in the dorms at night. One night the boys in the most senior dorm (me, Ian, Steve, etc.) decided to raid one of the more junior dorms next door. Unfortunately, the occupants of this room got wind of this and when we tried to get in after lights out the door was firmly jammed shut. There then followed two hours of every conceivable assault on the door to their room. We tried kicking it, charging it with a bench, picking the lock, and putting lighted matches through the keyhole. I’ll never forget the final scene when Eric, alerted by the commotion, walked up the stairs in his dressing gown, took one look at the situation and shouted,

‘Who’s the instigator of all this?

I knew it couldn’t have been me because I didn’t know what an instigator was.

The teachers really did have to put up with a great deal of outrageous behaviour. They were remarkably tolerant all things considered.

During the course we gave a concert in the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Happisburgh (17), with Sybil Olive playing the Beethoven Romance in F for Violin. The course ended and we gave the usual concert on our return at Bushloe High School repeating the Happisburgh program.

The new term began, and, back with the Senior Orchestra, I took part in a concert in Leicester Cathedral on the 13th September. We attempted to play Semiramide but the daunting opening for the horn section proved too much for us. After the concert Del Mar took the decision to withdraw this item from the forthcoming summer tour even though the programs had already been printed. (Instead, a printed flyer was inserted into the tour programs claiming that a key horn player had been taken ill!).

The following week we embarked on a major tour to Austria. We preceded this by stopping in London to record Candide for the programme ‘How It Is’ for the BBC. We were squeezed into a very cramped studio and were astonished to discover that it was the same one used by the BBC for ‘Top of the Pops’ because it looked much bigger on the TV.

We gave our final pre-tour concert on the 20th of September at the Fairfield Halls in Croydon, (18), spent the night in Dover and departed for Austria the next morning.

By now, like most of my friends, I was very fussy about which bus I was going to travel on. There were a number of factors to take into consideration:

1) there was usually an ‘in-crowd’ bus. This was the bus to be seen in if you were cool. Wimps were discouraged.

2) you didn’t want to sit in a bus with important members of staff such as Eric if possible. Such teachers restricted one’s ability to fool around.

3) the further towards the back of the bus, the cooler you were.

4) the ‘in-crowd’ bus was going to do all the dirty singing. This was a new phenomenon to me but one that I quickly got into the spirit of. We had our own versions of rugby songs that would make a prostitute blush. We would make them as rude as we could get away with. I used to particularly enjoy seeing girls and ‘shy’ boys cringe with embarrassment when we went too far.

If you were there you’ll certainly remember the old favourites – ‘All the nice girls love a …….’; ‘She came from Glamorgan with…..’; etc, etc.’

On all these trips Robinsons of Hinckley supplied the buses. We got to know the bus drivers as well as we knew the staff – in fact sometimes better. We all tried to get ‘in’ with them because we knew they could get items for us that weren’t always available. Sometimes they were able to buy beer or fags on our behalf if it was otherwise difficult; on other occasions they could be persuaded to take us out on the bus for a night’s bar-hopping. When we were abroad they even managed to get one or two of us into night clubs (even strip joints!).

During the journey we lived on fruit pies, crisps and apples. I guess this was because they were very compact to carry and had a reasonable shelf life. Once, when we were loading up some of these items in boxes at St. Margarets a dog came by and peed on one of the boxes of apples. The boys who witnessed this immediately swapped it with the one due to be loaded onto the bus behind.

Whenever we went on these tours there were usually three buses to take all the staff, players and instruments. In the early days, the back few rows of seats in Bill’s bus were removed to make space for all the instruments and stands. Eventually, even this space wasn’t sufficient and we included a separate instrument ‘van’ (in practice, a large lorry) in the convoy. After each concert we were all supposed to chip in and help pack all the instruments away in the van. There never seemed to be an end to the amount of percussion equipment of the most awkward shapes and sizes that had to be manhandled from van to stage and vice versa; it was a right pain in the backside. I always had to wrestle with my conscience about whether to give a hand with all this stuff or not. Sometimes, I’d do it because I felt guilty, sometimes I wouldn’t because it wasn’t very cool to be seen lugging these things around.

As the bus travelled through Germany I heard our resident barber’s shop quartet for the first time. This consisted of four lads from the trombone and bassoon section – Roger Harvey, John Turner, Martin Slipp and Maurice Turlington singing in what to me seemed like perfect four-part harmony. I was astonished at how good they were and couldn’t understand how they had learned to sing like that. Their best song was an arrangement of ‘I remember you’.

The Austria concert schedule was:

25th September – Linz (Diesterweghalle) (19)

26th September – Eisenstadt (Haydnsaal) (20)

27th September – Leoben (Kammersaal Donawitz)

28th September – Graz (Stepheniensaal) (21)

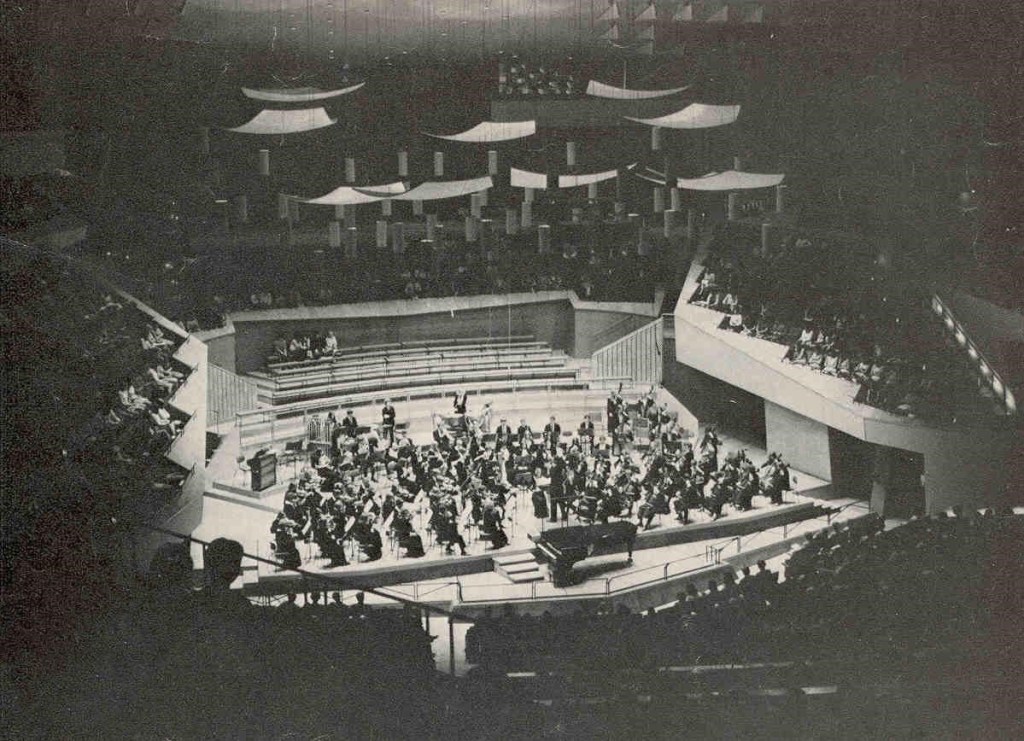

30th September – Vienna (Grosser Sendesaal) (22)

1st October – Vienna (Musikvereinsaal)

2nd October – Salzberg (Grober Saal des Mozarteums) (23)

3rd October – Munich (Hochschule fuer Musik) (24)

We maintained pretty much the same program throughout the tour, and were fortunate in having Norman Del Mar with us as guest conductor and Nichola Gebolys as pianist.

On the way there, we had an interesting night in Frankfurt. About thirty of us had gone out to get smashed and had had a great evening drinking. We walked back over one of the many bridges that crossed the Rhine to return to our hostel. But when we arrived it was locked shut (not surprising as it was well past midnight). We knocked on the door and demanded quietly to be let in but no-one could hear us. Eventually, after a long wait, someone in a nightshirt turned up to open the door and let us in. He made sure that we understood that this was completely out of order. What made it worse was that Mr. Westcombe, much to his embarrassment, was with the group and was supposed to be responsible for us.

The next day we heard that Lambert (one of the staff string teachers) had left his suitcase on the dock in Dover. We were constantly reminded of this when we saw him walking around in the same clothes for the duration of the tour.

We soon had a bit of trouble with the accommodation. We were due to stay in a hotel en route to our first scheduled concert venue in Linz. But, apparently, the hotel proprietors had been forewarned of our loutish behaviour in Frankfurt and refused to put us up. So instead we had to stay outside the city in a youth hostel in a place called Passau.